This is an excerpt from George Wallace’s essay The St. Austell Landscapes.

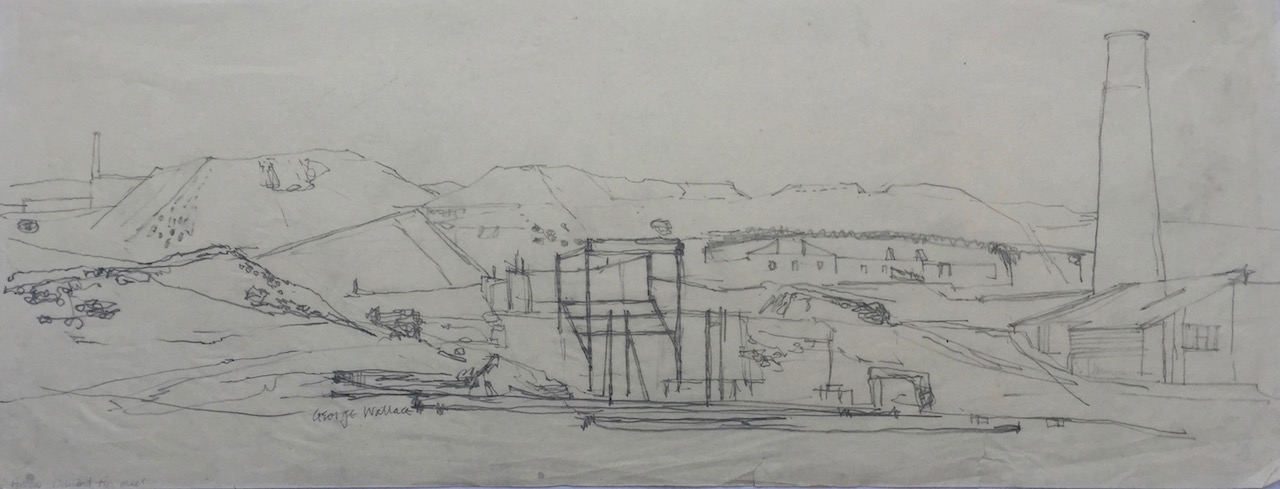

The St. Austell etchings have not always been recognized as landscapes. These prints and many other prints and drawings of similar subjects are the result of visits to a specific, if rather a strange landscape. I think of them as sharing something in common with 18th and 19th century Romantic landscapes, which record the pervading mood as well as the distinctive texture of a particular place. Maybe I should try to give some idea of how they came about.

From 1949 to 1957 we lived in Cornwall and I taught in the Falmouth School of Art. The landscape of Cornwall is very rugged and has been celebrated since Antiquity for its deposits of tin and other minerals. As a result of centuries of mining it is covered to an extraordinary extent with ruined mine workings, which I found fascinating to draw. To my students these ruins were so commonplace as to be unworthy of notice and they found my enthusiasm for drawing them yet another of their teacher’s amusing eccentricities. Their comment was “if you like that kind of stuff you should visit the clay pit workings at St. Austell”. I took their advice and found an extraordinary landscape.

The china clay deposits at St. Austell were accidentally discovered in the 1780’s. It proved to be one of the largest kaolin deposits in Europe. Kaolin or china clay is found in disintegrating granite-like rock where small pieces of silica are embedded in fine clay. It is extracted by washing down such rock faces with high pressure hoses and collecting the resulting slurry in large ponds where the particles of silica sink to the bottom, while the kaolin remains in solution in the water. The hosing down of the disintegrated feldspar has created gigantic pits. Because of the irregular distribution of the kaolin, these pits are sometimes isolated and sometimes are clustered together in interconnected groups.

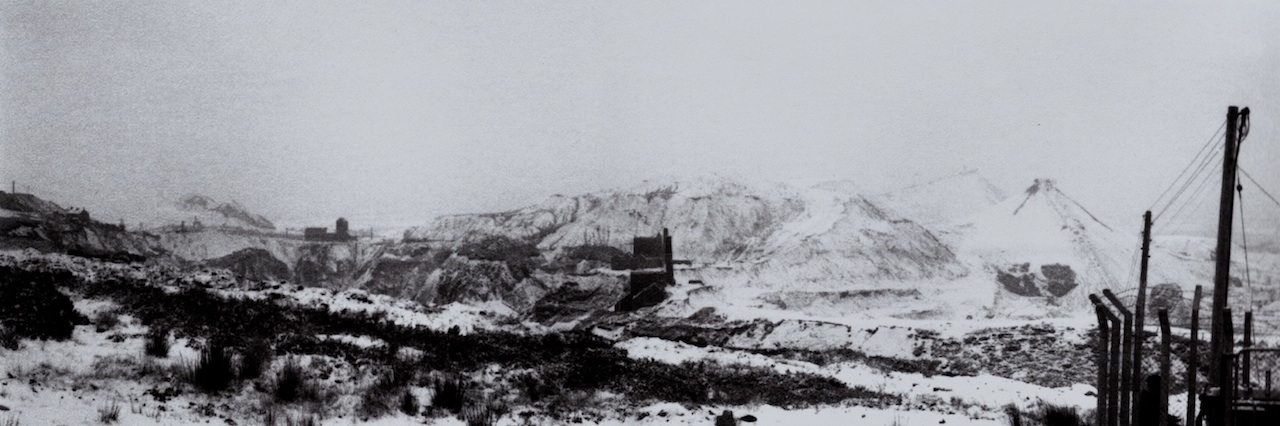

Man-made landscapes are sometimes characterized by more or less lucid geometric patterns, but at St. Austell no such patterns are present for here everything is determined by the location of the kaolin which is arbitrary and largely unpredictable. The capricious and irregular character of the whole undertaking is one of its great picturesque charms. The pits that are being worked have steep gleaming sides and can be identified at a distance by the great cones of white silica, which has been dredged from the settling ponds and carried out of the pits on skip ways. In addition the water in those settling ponds is a startling opalescent turquoise blue.

This was the dramatic industrial landscape that my students’ suggestion had led me to. I was over-awed by the transformation of so large an area of countryside. A transformation brought about entirely by the search for china clay, but which in the process had brought about an astonishing variety of picturesque images, often huge in scale, sometimes dramatically coloured and almost always richly textured. It was an environment which might be viewed from above as a series of very large precipitously walled excavations that dwarfed the men working in them or which also might be viewed from within and below, where they become great amphitheatres; some with large strangely formed columns standing in them. It was a vast eroded scene; at times sinister but entrancingly varied. It has proved to be unforgettable!

These visits came to an end in the spring of 1957, when I resigned from the Falmouth School of Art, and we came to Canada. I have never been back to the St. Austell workings. However during that interval, images of that strangely surreal landscape have continued to surface from my memory in the form of drawings and prints.

A description of these dramatic landscapes by Malcolm Ross-MacDonald, one of Wallace’s Falmouth students:

Geo discovered the St Austell claypits for us – this was before Health and Safety insisted the spoil tips be levelled and the beautiful moonlike landscape destroyed. In those days it was a ruthless and implacable country where everything was subordinate to the winning of kaolin, or china clay. You could walk along roads that ended abruptly in a wire fence, just a few yards short of a 150ft drop into a vast white pit…The land was littered with things that had outlived their use – rope, hawsers, rusted rail, little trams on bogeys that once hauled the waste up the sugarloaf ‘barrows’ that dominated the landscape …

We spent days walking and sketching in this wonderland, with Geo, and later on our own.

The Remembered Landscapes of St. Austell

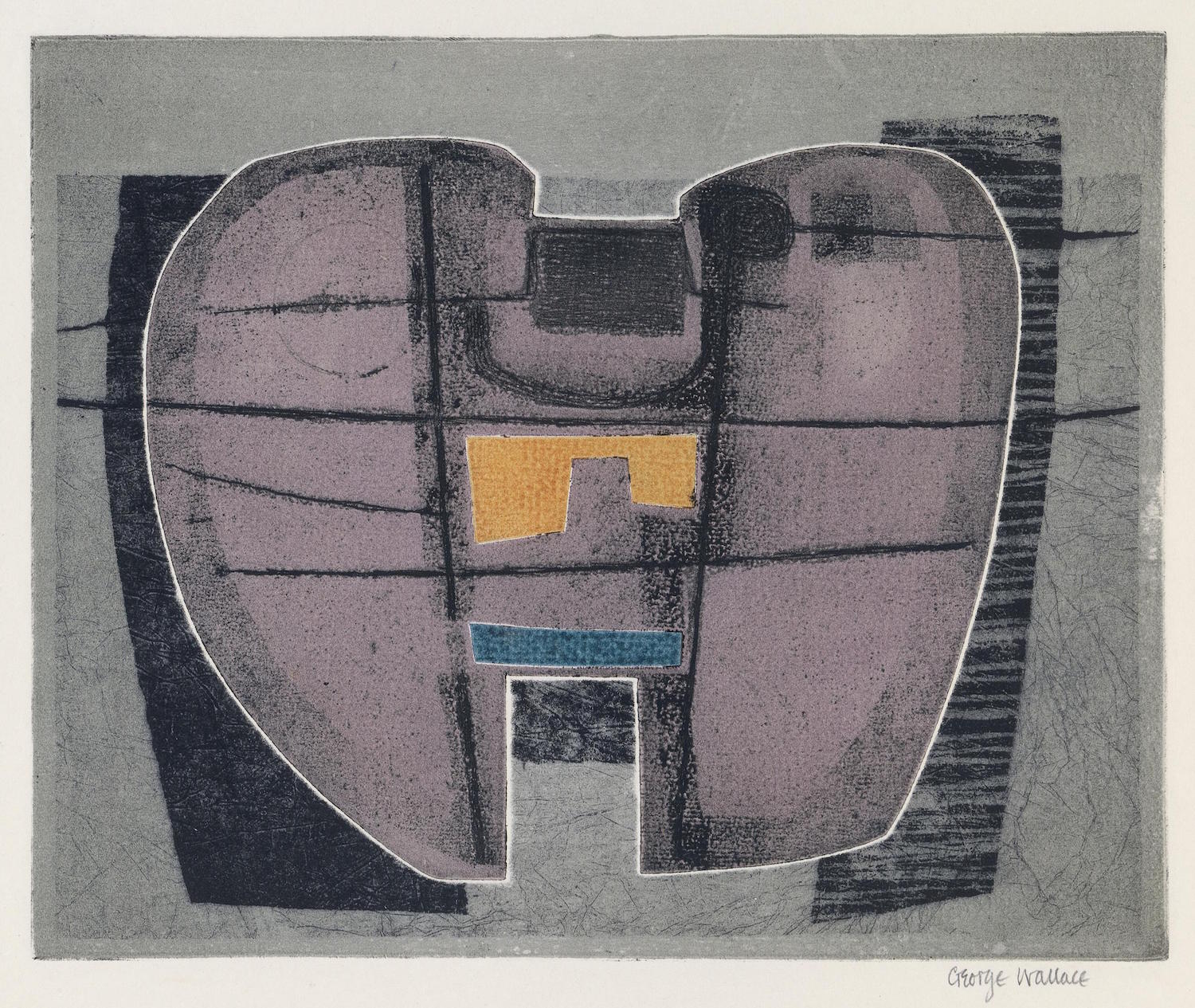

In the earliest of Wallace’s St. Austell work a clearly recognizable landscape emerges with a horizon and other identifiable features, but this quickly evolves into pure abstraction. In the prints from the 1950s you may see the influence of the Cornish artists of the 40s and 50s, of Barbara Hepworth’s sculptural forms, and Graham Sutherland’s abstract depictions of the rugged landscapes of northern England. Remarkably, Wallace continued to make drawings, watercolours, monotypes and etchings from memory, developing these increasingly abstract themes for the rest of his life. There are two portfolios of the St. Austell landscape etchings dating from 1973 and 1997 – an indication of the continuing importance he placed on this work.

Greg Peters writes in Images of Vulnerability:

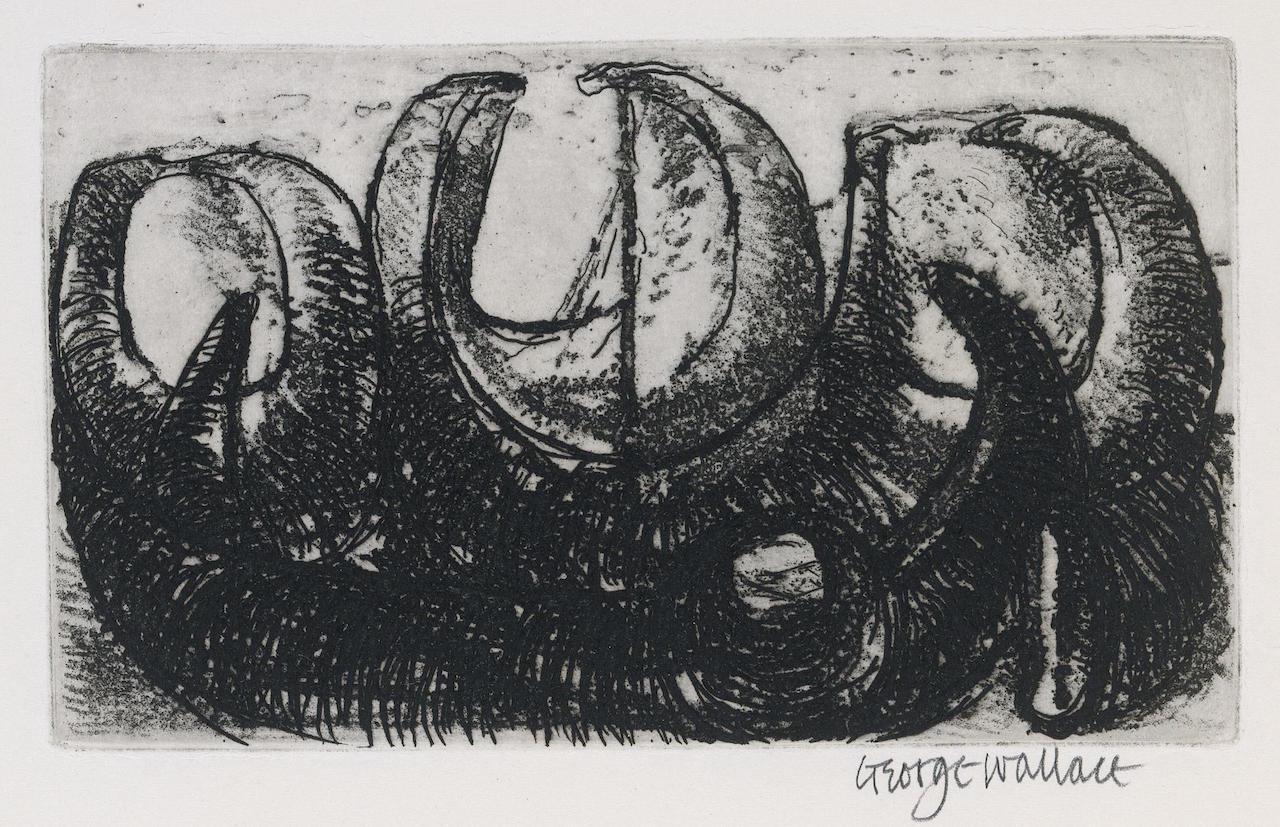

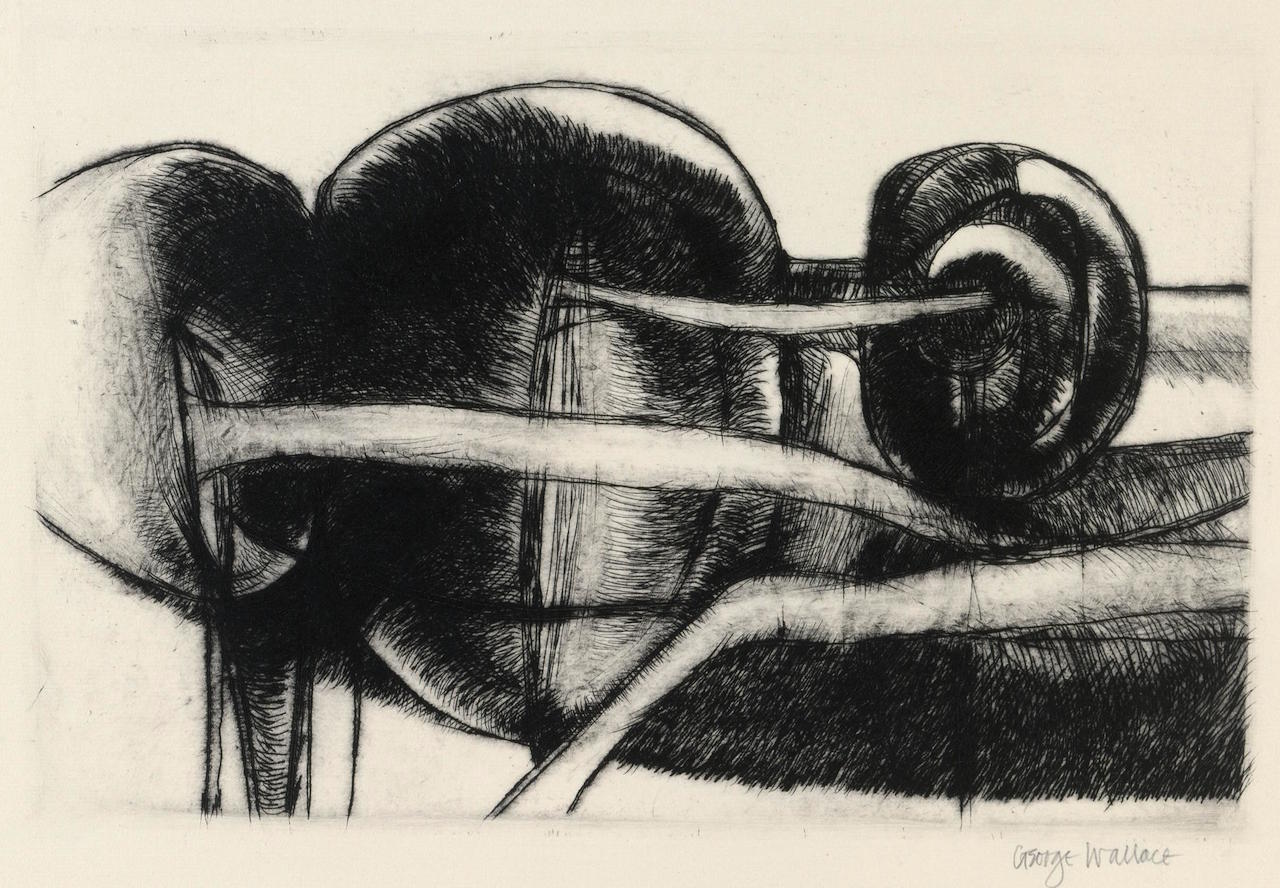

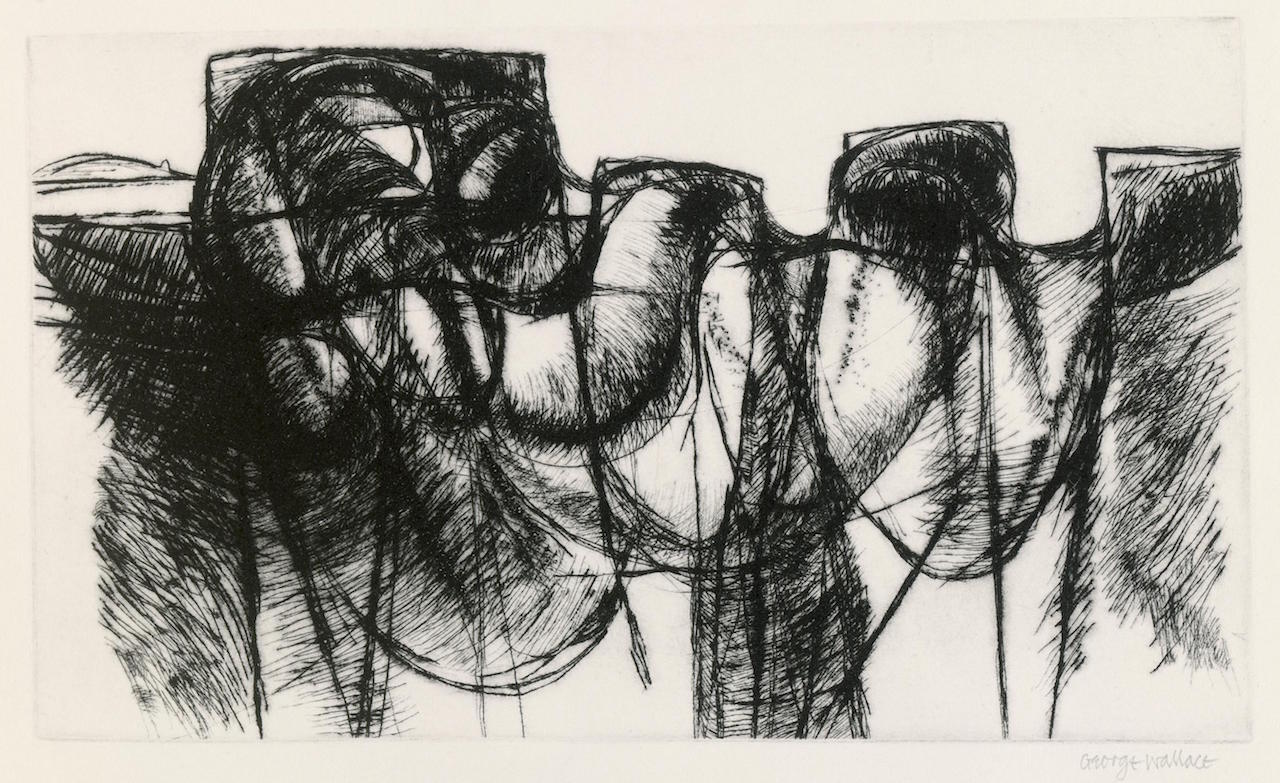

Beginning in 1971, George Wallace again turned to the most private images within his art, the mysterious forms of St. Austell. Gone are the severe, abstract designs. Most of the etchings contain both hard and soft grounds, and the monotypes have a thick, almost washed character. A different handling of both soft ground and drypoint gives these prints an impression of greater depth than the earlier landscapes, and Wallace has concentrated his focus on the forms within the earth itself. This is particularly true of the etchings comprising the “St. Austell Portfolio”. Deliberately avoiding customary spatial references, Wallace offers a microscopic examination of shape.

Initially, this can be quite disturbing for the spectator. The ‘ground’ has been quite literally cut out from under him, and he may find difficulty in securing a place to stand in relation to the image. Some shapes even appear to threaten because of their proximity. A close inspection illustrates how radically the artist has shifted his point of view. In the St. Austell and Redruth graphics from the mid 1950’s, the images are of a dead world. The mystery surrounding some of these objects is contained in the dark shadows, the mystery of the mechanical ghost which tore the ground apart. With the more recent etchings, however, an existence slowly materializes from the battered earth; live organs clearly begin to take shape. In “Large Excavations”, for example, the mines burrowed into the face of the cliff take on the appearance of the chambers of a gigantic heart.

The uneasy impression of growth and movement gives these prints their special quality. Pod structures appear to quietly develop in several of the etchings from the portfolio; sexual shapes interact in the “Twin Forms” etchings. Everything remains silent and brooding, but these are soft materials, subject to slow but inevitable change.

It would certainly be a mistake to view the temperament behind these landscapes as Arcadian. Wallace concentrates on the force and vitality of nature, but nature can just as easily have the effect of being sinister as being comforting. The artist is drawn to the torn apart landscape of St. Austell. In every case, ‘nature’ is always stripped bare, permitting the same presence to emerge.