I was born in Sandycove, South County Dublin on June 7th, 1920. My father was an engineer in the Department of Posts and Telegraphs, who had married my mother in 1917 when they were both rather elderly. I was their only child. This meant that as a child I was very much on my own and began at an early age to amuse myself by making drawings. When I went to school I was a complete duffer in part because I could not understand what I was supposed to do, but also because there seemed to be so many more interesting things to do than lessons. The mile long walk to school and back or the occasional days, when because of the weather or being sick I stayed at home all day, were always much better than anything that happened in class. As a result, drawing was the only activity in which I showed any ability in school and that was not much approved.

I was lucky after 1933 to go to St. Columba’s College, because there I began to read voraciously, and the art master was not only quite a good water colourist but, more important, he was himself trying to learn more about the subject. Hence, in the art room there were always books on modern art which we rummaged through, and this way came to know something of 19th and 20th century painting.

Art was not a school subject but an “extra” for which one’s parents paid an extra fee. This meant that to take art immediately defined one’s distinctiveness, for on one day of the week one did not do compulsory games. We who took art quickly learned that art and literature were subversive activities, not practised by middle class Irishmen such as our parents and their friends, but exclusively by heroic and eccentric Frenchmen. This does much to explain our shock and excitement when our art master brought us to visit Miss May Guinness, who had been a pupil of Van Dongen’s in Paris before the First World War. She lived in an attractive early 19th century house near the school. The walls of the rooms startled us, for they were painted white. One hallway was a lilac colour, the floors were covered with Persian and Afghan rugs, and the walls of every room were hung with amazingly vivid paintings such as none of us fifteen year olds had ever seen before. Most of them were Fauves paintings, though I remember a Bonnard interior, a Rouault watercolour of a working class suburb and a collage by Braque. More amazingly, Miss Guinness had met these people and even thought that Matisse was arrogant and self-important! How fortunate I was to see my first modern paintings in a private house and not in an art gallery where one example of each would have been set out to expound some dreary notion of Art Historical development or contemporary trends.

I went into Trinity College Dublin in October 1939 to read philosophy as a preliminary qualification towards becoming an Anglican priest. This was a vocation that had fallen upon me during the turbulence of puberty and which I had lost by the time I entered Trinity. However a vocation which was so enthusiastically endorsed by my family and relatives was hard to escape, particularly as I had no idea what else I might do. So I took a degree in philosophy and did a little more than a year of theology, before I escaped by qualifying as a school teacher. During this time I continued to paint and draw and made some small wood carvings in imitation of those of Barbara Hepworth.

I first taught at St. Peter’s College, Radley outside Oxford, which was a sister foundation of St. Columba’s, and there I met Paul Feiler, a painter who had trained at the Slade. A year or two later he went to teach at the West of England College of Art in Bristol and persuaded me that if I wished to paint I should go to art school. I had by then married and if Margaret continued to work such a return to school seemed economically possible, a situation slightly modified by the birth of our first child about a year later!

I was a student of painting in a department dominated by three painters: George Sweet, Paul Feiler and Bernard Dunstan, who had all been trained at the Slade. This meant that we drew at small scale, “sight size”, thought of drawing as an investigatory tool, not as an end in itself and believed that paintings were usually made from drawings. Everything tended to be at very small scale, in part because after the war art supplies were very hard to buy. I learned to etch in Bristol but you couldn’t buy sheet copper and all our etchings were done by grinding down old plates of pre-war students. You looked in the bin for small plates that had been lightly etched!

Towards the end of 1949 I went to teach in the Falmouth art school in Cornwall and it was there that our two other children were born. There I taught painting, drawing, print making and a little sculpture. During the time I worked in Falmouth I did a considerable amount of painting and drawing and experimented with various methods of etching. I exhibited in Dublin, London and Bristol. About 1955 I became interested in the wrought and welded sculptures of Reg Butler and went to the local technical school to learn how to weld. Before I came to Canada in 1957 I had made one welded sculpture.

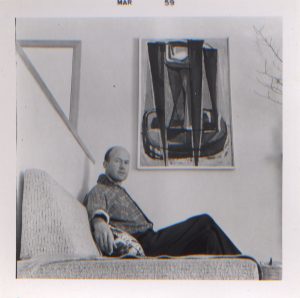

I landed in Montreal in July 1957 into a world of amazing kindness. Victor Waddington had shown paintings of mine in his gallery in Dublin and gave me an introduction to his brother George who had recently opened a gallery in Montreal. I also went to Ottawa and visited Alan Jarvis. It now seems almost unbelievable that an unknown newly arrived painter should have been entertained and advised by the director of the National Gallery, but that was Alan Jarvis. He gave me introductions to Barry Kernerman who ran the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Toronto and to Douglas Duncan. I visited Douglas Duncan a week or so later and characteristically he bought two prints from me. I had intended to travel across to the west coast, but I went to visit Kildare Dobbs who had been at school with me in Ireland, and as a result I stayed in Toronto. During the first year in Canada I taught at Ryerson Polytechnic and the next two years at Blakelock High School in Oakville. During that time I had exhibitions at the Waddington Gallery in Montreal and the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Toronto. In 1959 I taught part time at McMaster University in Hamilton and became a full time staff member in 1960.

In that year Waddington sold the sculpture that I had brought with me from Ireland and I used that money to buy a welding torch and regulators, and I began to weld in our suburban garage in Oakville. The first of the life-sized figures was John McMenemy’s Lazarus which is made from packing case strapping. At that time, while we still lived in Oakville, I used to take walks along the Canadian National railway tracks towards Bronte. It was a stretch of track used by freight trains bringing scrap to the steel mills in Hamilton. One day I came across part of a coil of steel strapping lying by the side of the tracks. The extended coil lying in the weeds suggested the description of the grave clothes found by the disciples in the tomb after the Resurrection. I brought the strapping home and it is part of that Lazarus sculpture. The unravelled coil evokes the Resurrection just as the raising of Lazarus prefigures it. I like such pre-configurations or reverberations of feelings.

Sculpture because of its size requires a more public existence and should speak more specifically, more clearly, even more politically, than the more intimate voice of painting or drawing, but it must also have some reverberation if it is not to look like 19th century public statuary.

I don’t think that the mood of these sculptures (there are now eighteen pieces using life-sized figures) has changed much over the last twenty years. Two of the figures certainly have something to do with mourning for the death of my mother and six years later for my father but the others come from a less specific mood of the times, as the angry legless man is a relic of Vietnam. Wars and bloody minded tyrannies have remained a consistent part of our mental landscape throughout that time.

You notice that these comments are against a notion of sculpture as pure art or a formally perfect arrangement and are also against it as private whimsy. Instead they express a belief that sculpture, like poetry or prose, may speak to present issues without the rigidity of a “good soldier” following the party line and without adopting “the preacher’s loose immodest tone”.

(Text from the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, ”George Wallace: Sculpture and Graphics” 1983)