George Wallace learned to etch during his time as a student at the West of England College of Art, as he tells us in his A Note on Printmaking. Printmaking was an enduring interest throughout his artistic career and technically the most accomplished of all his work. While teaching at the Falmouth School of Art he experimented not only with the various techniques of etching – hard ground, soft ground, deep etch, and aquatint, but also with other forms of printmaking such as drypoint, lithography, woodcut, and monotype. Two broad themes emerge at this time that continued to inspire his work throughout his life. These are the abstract landscapes of St Austell and the figurative images of the tortured man – heads of soldiers, or the incarcerated – much darker in meaning, and relating to the subject of death and “bloody minded tyrannies” in much of the welded steel sculpture of the 1960s.

It is quite apparent from the size of the galleries here that etching and monotype were Wallace’s favourite printmaking techniques. Etching is a medium for printing and disseminating the work to a larger audience; monotype is almost the opposite, a one-off printmaking technique perhaps more analogous to painting. Wallace exploited etching’s potential for revision, printing very few plates as limited editions (limited editions were essentially invented as a marketing tool), preferring to re-work the plate sometimes years after it was first printed, to create several radically altered states of the original. This is not to say he didn’t keep records of the numbers of prints pulled. He kept scrupulously detailed information about each print he made, including the type of paper it was printed on.

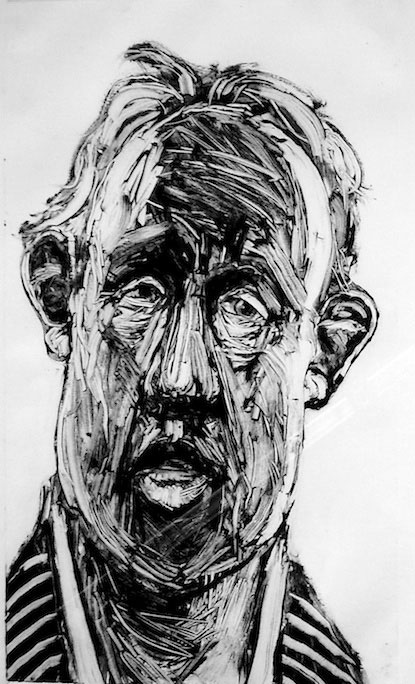

It is interesting to see the transition between the early hardground etchings of quite conventional subjects to the more abstract and expressive deep ground etchings made in Falmouth. The later deeply etched prints of helmeted men have almost sculptural qualities that prefigure Wallace’s welded steel sculpture. The St. Austell china clay pits in Cornwall were man-made landscapes that he discovered in 1955, setting off an inexhaustible well of imagery in which he explored the abstract, and which always ran in parallel to his figurative work. We also see the genesis of a Christian imagery in the art of George Wallace. The subjects of Peter and the Cock, and of Lazarus, first seen in prints dating from the mid-50s are to reappear as themes throughout the following decades.

The monotypes were made mostly after he retired to Victoria in 1985. He records over four hundred made between 1988 and 2005. In contrast to the etchings, the monotypes give an impression of spontaneity similar to a rapid sketch. As Wallace has stated, the notion of wit is important to the effortless capturing of the moment in a work of art, and so the monotype is perhaps more apropos to his satirical subject matter like the mug shots of businessmen and the dispassionate couples depicted. You can read the artist’s A Few Brief Words on the Art of the Monotype to discover more about his fascination with the technique.

To understand the work of George Wallace one must also appreciate his love of the craft of making art. He was extremely knowledgeable about the techniques of printmaking; he ground his own pigments, made his own inks and took pride in using the most expensive papers. He knew a great deal about the history of printmaking, the artists who practised this particular art form and who developed its techniques. He was strongly influenced by the German Expressionist printmakers, and by Rouault, Goya, Blake and Degas.